The word “innovation” is brandished everywhere. It’s a compelling concept and every day we enjoy working with our clients to deliver them its promise. According to Google Ngram Viewer (which calculates the frequency of word use in publications between 1800 and 2008), “innovation” was used 73% more frequently in 2008 than it was in 1908. The increase was particularly steep between 1962 and 1974 and then again between 1993 and 2006. Why is it so popular? What are the different types of innovation so that we can be more specific when we use it? How are innovation concepts and theories commonly misused and how can they be helpfully applied instead? To answer these questions, I’m going to walk through highlights from a recent New Yorker article and examine Clayton Christensen and Don Norman’s innovation theories.

Why so popular?

Jill Lepore recently wrote a provocative article on the way society uses the term innovation – and particularly Clayton Christensen’s “disruptive innovation.” An American History professor at Harvard, she lays out an interesting historical review of the use of “innovation,” contextualizing its popularity within increasing global tensions and economic downturn. Change and improvement were synonymous in the 18th and 19th centuries when words like “progress” and “evolution” were more prominent. However, in the 21st century, she suggests society uses “innovation” and “disruption” to instead “skirt the question of whether a novelty is an improvement: the world may not be getting better and better but our devices are getting newer and newer.” This is an unsettling conclusion, pointing out the desperation and insecurity of modern day. It’s our challenge – and responsibility – as designers and innovation leaders to deliver novelty that also has a positive impact on society. A deeper understanding of the types and methods of innovation can help us reach this goal.

Clayton Christensen helps us balance two types of success

Every innovation strategy firm has their own definition of innovation, so for today’s post, I’m going to take us out of the design/innovation industry and bring us into academia. Clayton Christensen of Harvard Business School is the author of Innovator’s Dilemma, which examines how established companies can do everything “right” yet still miss out on market opportunity and even fail. Competitors (often startups) “disrupt” by offering a lower-quality, cheaper product and therefore tap a new market.

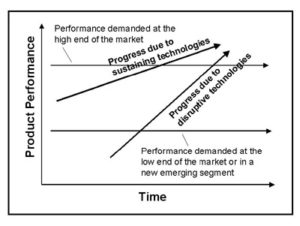

How can Christensen’s theory strengthen our work? While many brandish the word “disruption” in a sensational and convoluted way (see Lepore’s full article for more on that topic), it is actually a defined phenomena that can be avoided. We can help our clients create strategies to avoid being vulnerable to disruption or even to disrupt a competitor themselves. We can also calm client’s fears that if they don’t disrupt the market, they will be disrupted themselves and therefore fail. There are other options; being disrupted doesn’t mean complete failure. Christensen has a concept called “sustaining technologies.” For example, U.S. Steel was disrupted by minimills, but the company did not fail as a result. Yes, it missed out on additional opportunity, but it still succeeded by focusing resources on a premium product (sustaining its technology) that minimills couldn’t threaten. Finally, the above relates to established clients, but emergent clients can also benefit from more deeply understanding the disruptive landscape. It’s important to caution that while Innovator’s Dilemma paints a romantic and appealing picture of entrepreneurship, it is a theory that explains why established firms fail, not a theory as to how startups succeed. Disrupting for disruption’s sake doesn’t necessarily make a successful startup. We can guide our startup clients to form productive strategies that are both disruptive and sustaining, with short term and long term benefits.

Don Norman helps us choose the right methodology for the job

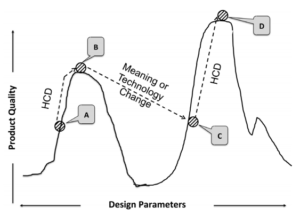

Don Norman formerly of Northwestern University (among other faculty positions) breaks down innovation into “incremental” and “radical” and examines who produces each and how. Incremental innovation, similar to Christensen’s “sustaining technologies,” involves the steady improvement of product quality and is the most common type of innovation. Human-centered designers and design researchers contribute to this development process, identifying opportunities to make the product more usable, useful and desirable. Radical innovation, the more exciting but much more rare of the two, involves a technological breakthrough driven by an inventor’s exploration. His position that HCD does not create radical innovation has been met with much critique and spurs interesting discussion. In the end, like Christensen, Norman’s theories similarly acknowledge how thrilling strokes of genius as well as consistent and reliable progress are valuable to companies.

As for the application of incremental and radical to a client context, this distinction helps us choose and justify our methodologies. His classification clarifies what clients can expect from each approach: radical innovation will jump to new design parameters but will not immediately produce a superior-quality product while user research will improve the quality of a product but will not create technological breakthrough. Both contribute to intellectual advancement, but in different ways and with their own limitations. Norman helps us align client expectations with outcomes.

A Christensen and Norman recap…

The more we hear and are asked to deliver “innovation,” the more important it is to be clear about what we mean and what we can create. These two theories can give us helpful frameworks as we guide diverse client types through the messiness of change.

These are the rules of innovation we learn from Christensen and Norman:

Innovation doesn’t necessarily mean an improvement; it can just be newness. Make it an improvement.

Disruptive technologies have market advantage because they are cheaper, simpler and therefore are accessible to a wider audience

If you don’t disrupt, you can sustain. Sustainable technologies are also profitable and valuable to a business.

Established businesses can have disruptive or sustainable technologies. Emerging businesses can have disruptive or sustainable technologies. Generally, it’s easier for startups to launch a disruptive technology.

We know disruption happens and is something to be aware of. We don’t necessarily know how to avoid it or how to lead it.

Most innovations are incremental.

Radical innovations are very rare and hard to come by.

Human-centered design and design research create incremental innovations.

Technological invention creates radical innovation.